Feature Branches are great. I like using them. But sometimes, they are a terrible choice and get in the way of progress. Here is why.

Feature branches are a development practice where developers create separate branches in a version control system (like Git) to work on new features or bug fixes independently from the main codebase. This approach allows for isolation of changes, enabling developers to experiment without affecting the stability of the main branch.

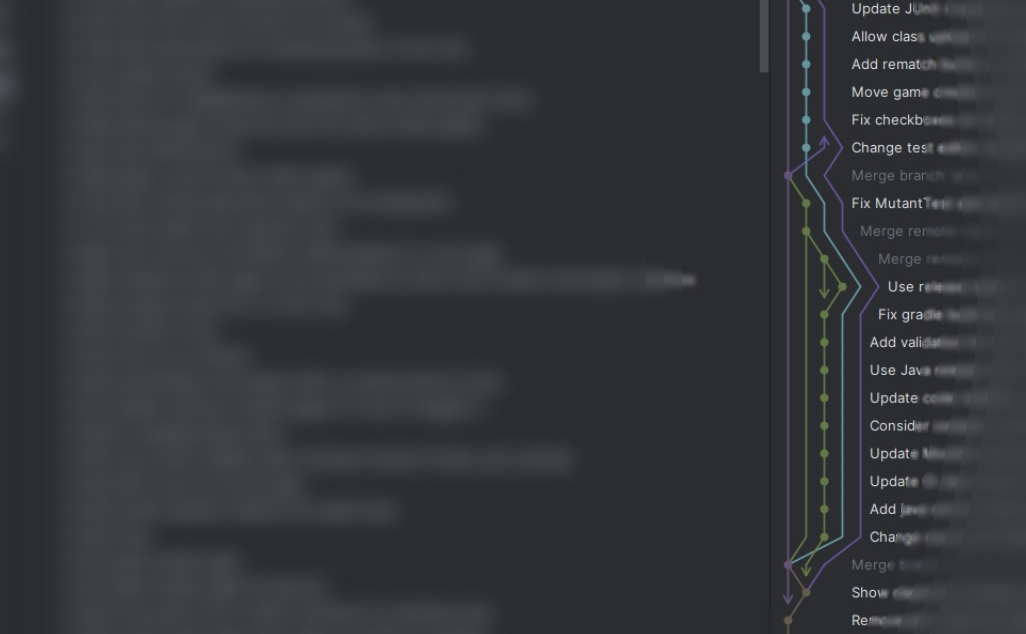

The typical workflow involves creating a new branch from the main code, working on the feature, and then submitting a pull request for review once the feature is complete. After approval, the branch is merged into the main codebase.

Feature branches facilitate parallel development and improve collaboration among team members. They are effective for teams working on multiple features simultaneously while ensuring code quality through reviews. [1][2]

The idea sounds great: Developers can work on different aspects of a project at the same time without getting in the way of other developers. The main branch remains stable, and changes are only pulled once they are complete, tested, and reviewed by other developers.

So why wouldn’t you want to use them?

The Problem with Feature Branches

In general, feature branches have a few drawbacks:

As branches diverge from the main codebase, integrating changes becomes increasingly difficult and time-consuming. This can lead to complex merge conflicts, especially with long-lived branches.

You can try to counter it by keeping your branch up to date with the main branch. This means merging and integrating changes from the main into your feature branch as often as possible. While this adds additional work, it helps with the final integration of the feature branch in the current product.

However, this will not work if multiple feature branches are around for a long time. They will diverge from each other, and whichever branch is merged last may come with many merge conflicts or integration challenges. This is not only time-consuming but also error-prone and may introduce bugs. [3]

In fear of these merge conflicts and integration challenges, developers get discouraged from refactoring. Even refactoring simple things can lead to divergences from other active branches and require tedious conflict resolution. Additionally, you might spot code that should be refactored, but because changing it is not part of your current feature, it will be deferred or forgotten.

The lack of refactoring ultimately leads to more technical debt and lower software quality. [4]

Another point is the delay in feedback and communication. Only at the very end, once the feature is implemented completely, do other members of the development team have a look at your code. Before that, you are not required to communicate your changes to the team. [4]

If, during review, it turns out that you need to take a different approach, a significant, time-consuming, and frustrating rewrite of the feature could be required. Even worse, if such things are not noticed during the review and the detection of substantial flaws is delayed until after the branch has been merged.

The lack of communication during development also leads to knowledge silos where only one developer knows the details of a feature or specific problem-solving approaches, hindering the team’s overall productivity. [5]

Why Feature Branches Are Bad for the MVP

The drawbacks discussed may be manageable, or even mitigated, if you’re aware of them. Compared to the potential chaos that alternative workflows could introduce, these issues are often worth tolerating. However, when developing a new product from scratch, the disadvantages of using feature branches become more significant.

A Minimum Viable Product (MVP) is a basic version of a product that includes only the essential features necessary to attract early adopters and validate a product idea.

It’s a development approach that aims to create a functional product with minimal resources, allowing teams to gather maximum user feedback with the least effort.

Collaboration and communication are crucial in the early stages of developing a new software architecture. There is no existing codebase to serve as a guideline. You often have to set up completely new parts and components to build your feature. These decisions have a lasting impact on the system’s architecture and should, therefore, be made in consultation with the entire team.

Feature branches tend to isolate developers, which can slow down the exchange of ideas and delay integration. When everyone works in separate branches, architectural decisions and design patterns evolve independently, leading to inconsistencies that are difficult to reconcile later. This fragmentation often results in duplicated effort, merge conflicts, or incompatible implementations.

In some cases, it can even lead to two developers implementing two different solutions to the same problem on their separate branches. Instead of building a solution that supports both use cases, discussing the concept as you develop it, the first approach to finish will be merged, and the other developer will have to address the problem. But aside from the issues that arise when merging, solving the same problem twice also costs time and resources.

For an MVP, speed and alignment matter more than perfect isolation. Rapid feedback and continuous integration are essential to ensure that all parts of the system grow together coherently. Working directly on a shared branch or using short-lived branches encourages frequent communication, faster iteration, and early identification of architectural issues. In this stage, collaboration and shared ownership of the codebase outweigh the benefits of isolated, long-lived feature branches.

Alternative Workflows

For an MVP, you can’t afford workflows that slow feedback and hide crucial architectural decisions. Instead of long‑lived feature branches, there are several collaboration models that keep the team aligned and the codebase evolving coherently.

Trunk-based development

In trunk-based development, most work happens directly on a shared main branch (often called main or trunk, thus the name). Developers commit small, incremental changes frequently, sometimes several times per day, and integrate them right away. This keeps the codebase as a single, up‑to‑date source of truth that everyone works against. [6, 9]

For an MVP, this model is powerful because it maximizes visibility. Architectural changes are immediately exposed to the whole team, which encourages discussion and fast correction if something goes in the wrong direction. Instead of discovering conflicting designs during a painful merge at the end of a long feature branch, incompatibilities surface within hours and can be fixed while the context is still fresh. This can save a lot of frustration.

Trunk-based development also fits naturally with continuous integration: every change is built and tested quickly, so you always know whether the current system is in a releasable state. [8]

Feature flags

Feature flags (or feature toggles) provide another effective alternative. Instead of keeping a large, unfinished feature on its own branch for weeks, the team merges the work into the main branch early and guards it with a flag. The behavior can be turned on or off at runtime, per environment, or even per user segment.

For an MVP, this pattern enables early integration without exposing incomplete work to the other developers or at showcases. You can evolve new architecture components in small steps, keep them compiled and tested with the rest of the system, and still have a stable product version available at all times. If a new architectural direction turns out to be wrong, you only need to remove the code behind a flag, not unwind a giant branch that has diverged from reality. This keeps risk low while maintaining a high frequency of integration.

But you always need to keep an eye out for dead code. At some point, outdated feature toggles have to be removed from the code. [8]

Short-lived feature branches

Sometimes, a team still wants the structure of branches. For example, to support code review or to group a small set of related commits. In that case, the key is to make feature branches extremely short‑lived. A short‑lived branch is created for a focused change, kept in sync with main, and merged back as soon as possible: Ideally within hours or a couple of days at most.

This approach preserves some benefits of isolation (you can experiment a bit without immediately affecting others) while avoiding the worst problems of long‑lived branches. Because branches exist only briefly, they don’t diverge far from the main, so merges tend to be small and straightforward instead of huge and risky. For an MVP team, this means you still get the safety net of review and small experiments, but architectural decisions remain visible and integrated almost immediately.

You really need to enforce the short-lived timespan of these branches, though. Otherwise, you will just end up the exact way we started: with normal feature branches.

A great way to do work with this approach is the following:

Every time you need to make a change that is necessary for your feature, but not directly linked to it, or affects other areas and components, you create a separate branch for it. [7]

For example: While you’re building a new form, you might realise that the existing input component doesn’t support things like inline validation messages or a compact layout needed for that screen. As you work on the form, you adjust the shared input component to handle error states, tweak its spacing, and add support for helper text. You might also address a minor accessibility issue in the shared modal that hosts the form. None of these changes is the form feature itself, but they naturally emerge as you implement it.

You can do these changes independently on a new branch and merge it. This way

- your feature branch will contain fewer commits and changes,

- possible problems or architectural decisions are addressed earlier, and

- everyone else in the project is already able to use the updated component, even before the feature branch for the whole form is merged.

Conclusion

In summary, trunk-based development with feature flags or short-lived branches offer alternatives to avoid the problems of long-lived feature branches during MVP development. Every team should experiment to find the workflow that best fits their dynamics and goals.

My advice: prioritising small, frequent integrations helps to keep everyone in the loop, makes architectural decisions more collaborative, and avoids unnecessary work and frustrating merge conflicts.

Sources

[1] https://martinfowler.com/bliki/FeatureBranch.html

[2] https://www.bunnyshell.com/blog/what-is-a-feature-branch/

[3] https://www.cloudbees.com/blog/pitfalls-feature-branching

[4] https://thinkinglabs.io/articles/2022/05/30/on-the-evilness-of-feature-branching-the-problems.html

[5] https://continusys.com/knowledge-silos-what-are-they-and-how-to-avoid-them/

[6] https://docs.aws.amazon.com/prescriptive-guidance/latest/choosing-git-branch-approach/advantages-and-disadvantages-of-the-trunk-strategy.html

[7] https://groengaard.dev/blog/avoiding-long-lived-feature-branches

[8] https://www.innoq.com/en/blog/2018/10/continuous-integration-contradicts-feature-branches/

[9] https://graphite.com/guides/trunk-based-development-workflow